Research shows that founder-led companies tend to outperform their counterparts in a range of areas, including innovation and long-term share price performance.

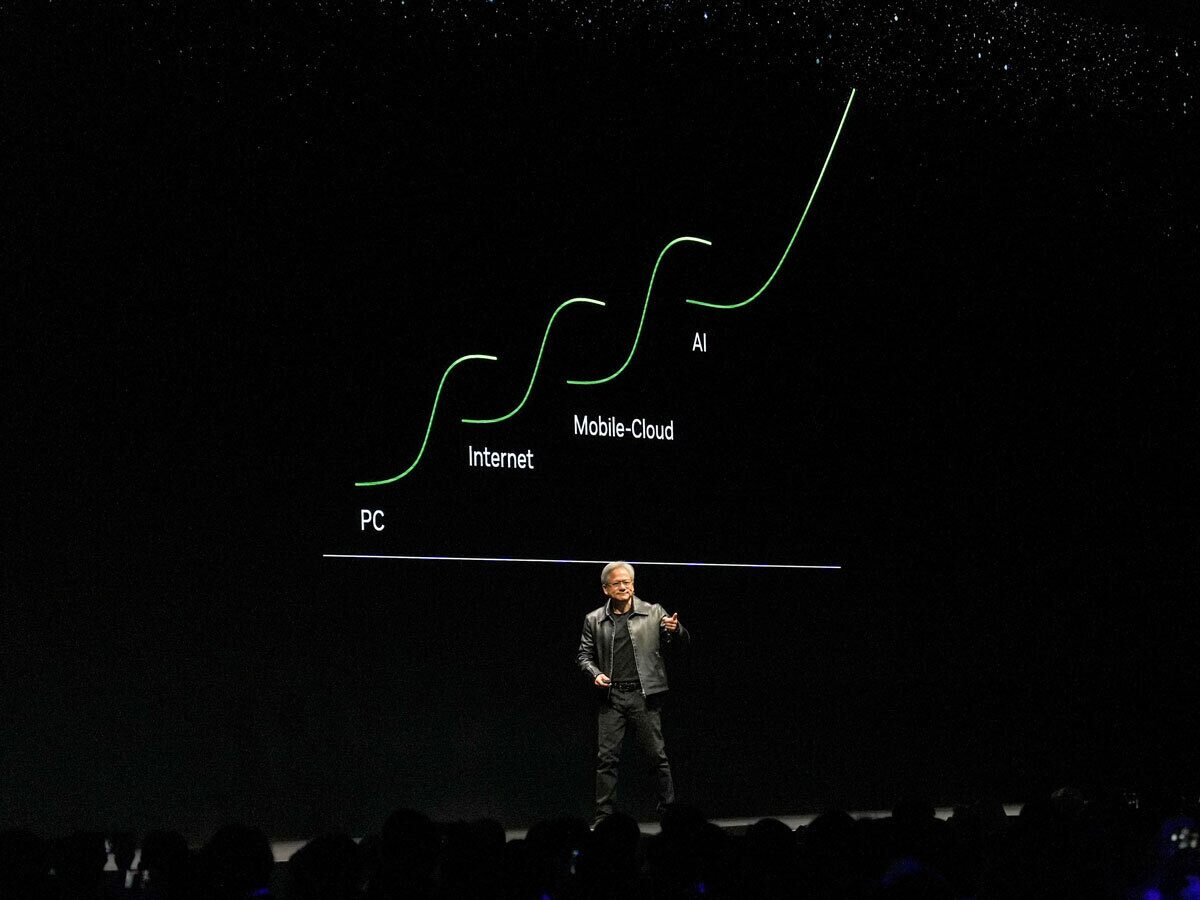

Today’s investing landscape is characterised by the disruptive impact of highly innovative companies. Understanding the long-term goals of these founders is key for investors seeking to grasp their businesses’ full long-term value.

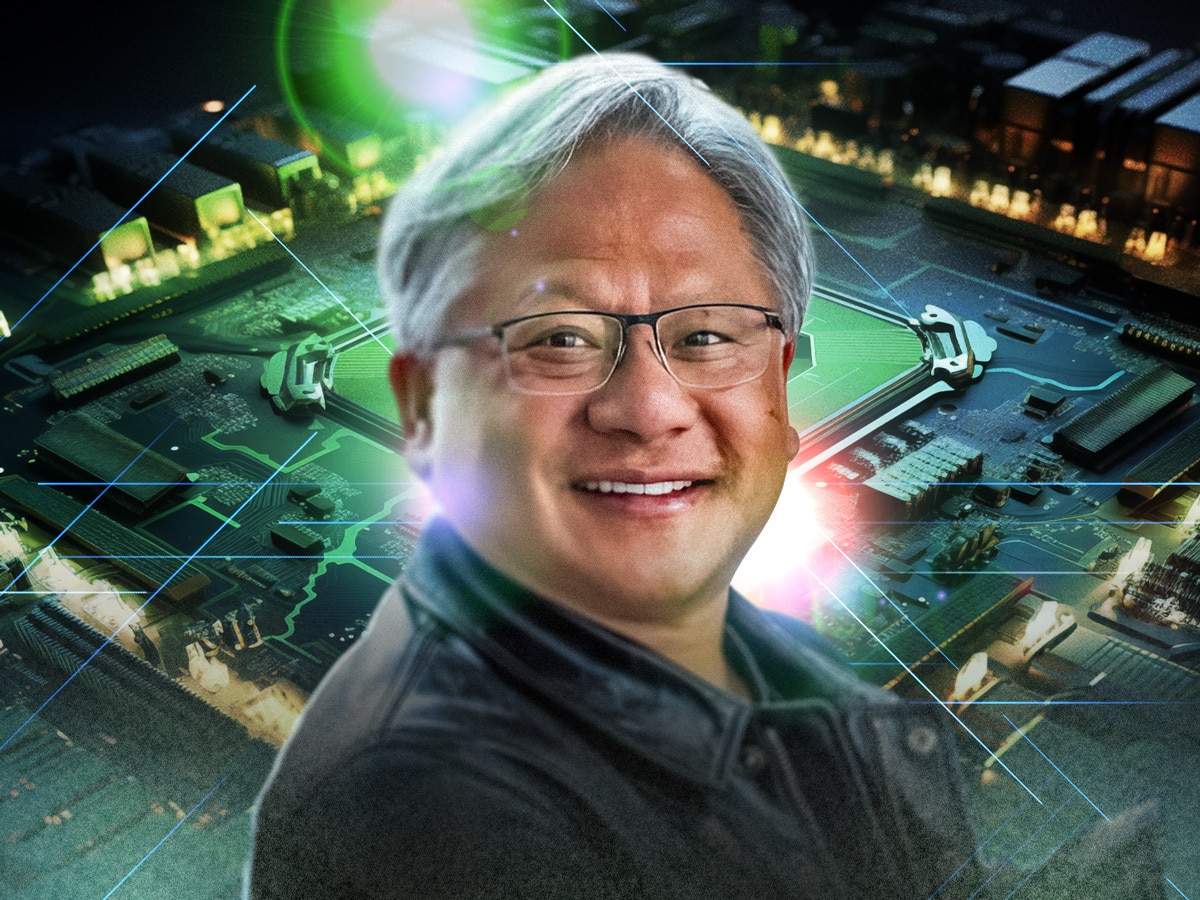

Having long held cult status among video gamers, Nvidia [NVDA] has become a household name in the last year thanks to the rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI). But the company might never have cracked graphics cards, let alone AI, without the courage and determination of its founder, Jensen Huang.

What Makes Jensen Huang Different? Huang’s leadership style is defined by perseverance and risk-taking. Huang met Nvidia’s two other co-founders, Chris Malachowsky and Curtis Priem, when they were working together at Sun Microsystems, which at the time was manufacturing computer chips. Huang was assigned to work with them from LSI Logic, which supplied the component semiconductors. The three became some of the first people to ever develop a graphics card — a chip that could be inserted into Sun workstations, enabling the display of computer graphics. On Sequoia Capital’s Crucible Moments podcast, Huang described Malachowsky and Priem as “visionary” engineers. But in the early 1990s, the architecture on which the two worked at Sun fell out of favour with the company. They left — and began trying to pry the reluctant Huang away from LSI Logic to start a business together. At this time, the PC revolution was beginning to gather pace, and gaming was emerging as a clear use case for increasingly affordable computers. “The capability, the graphics capability, the multimedia capability of the PC was non-existent at the time. There were no sounds, there were no microphones, there were no speakers, no video, no graphics. Basically it was a text terminal. And we thought, you know, maybe 3D graphics would be the thing that’d be really cool.” Despite the allure of staying in his steady job, Huang took a punt on this emerging opportunity. |

The Next Vision

In 1993, Nvidia was formed. Its founders’ drive to continually push the boundaries of possibility in computing was baked into its name, in the form of the acronym “NV”, standing for “next version”.

From the outset, this focus on innovation drove Huang and his co-founders as they racked up a series of breakthroughs. It wasn’t smooth sailing, however — many of Nvidia’s early products flopped, but Huang in particular brought determination and resilience to the equation, and the team continued to innovate and refine its offerings.

“We have had some setbacks, but I’m told I’m the hardest CEO to kill” — Jensen Huang, 1999

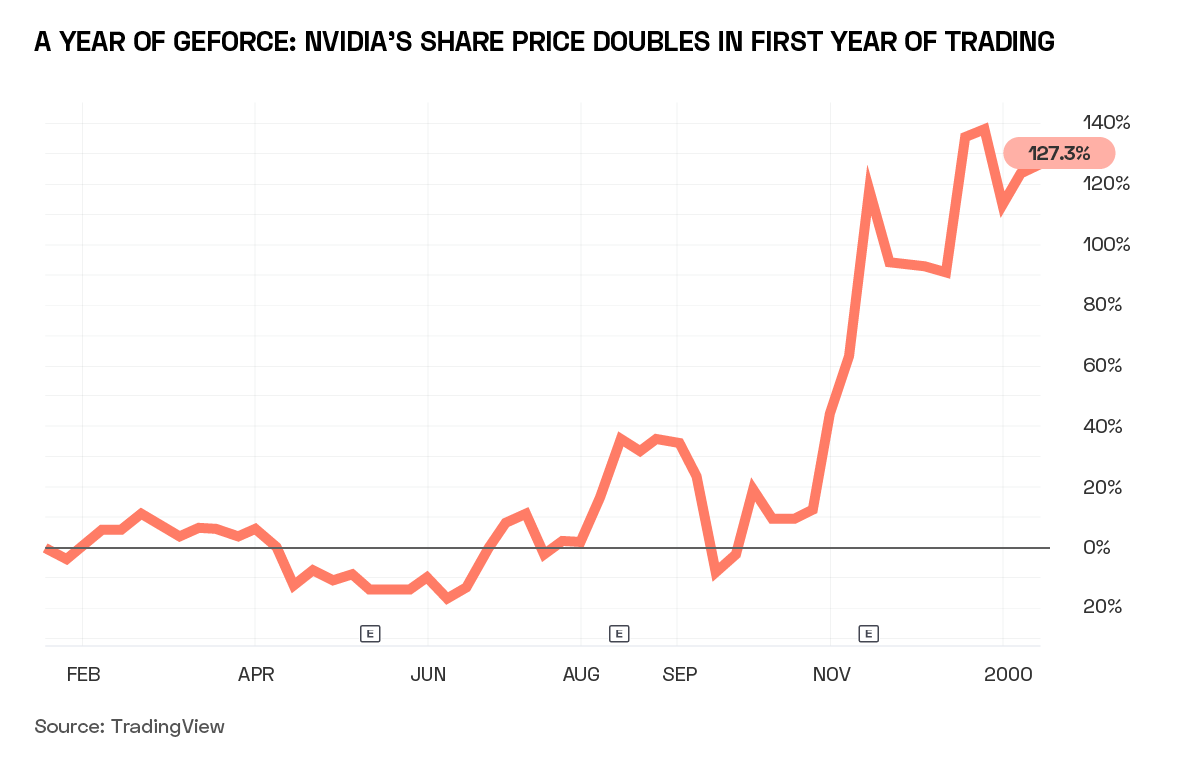

In 1999, Nvidia released the GeForce 256, which was marketed as the world’s first fully integrated graphics processing unit (GPU).

The GPU completely changed both gaming and computing parlance, as the acronym (which started life as a marketing slogan) stuck. GeForce 256 effectively took the heavy lifting involved in graphics processing away from the central processing unit (CPU), thereby reducing the load on the latter and massively increasing the complexity of games that could be run.

While Nvidia’s competitors (including Advanced Micro Devices [AMD], a previous employer of Huang’s) scrambled to create their own products to compete with GeForce, Nvidia was always one step ahead. Thanks to Huang’s unrelenting focus on the next version, Nvidia became the biggest name in computer graphics almost overnight.

One year after its January 1999 IPO, Nvidia’s share price had more than doubled.

Not Just a Game — The Pivot to AI

The parallel processing capabilities of GPUs were then brought to the worlds of science and research via CUDA architecture in 2006. This was a key milestone because it demonstrated that Nvidia’s programmable GPUs could be applied outside the world of gaming, at a time when Huang and the team were looking to diversify the company’s offerings.

This paved the way for what was arguably Nvidia’s most groundbreaking pivot. In the late 2000s, various deep learning researchers, including Andrew Ng, the Founder of Google [GOOGL] Brain, and Yann LeCun, now VP and Chief AI Scientist at Meta [META], started to recognise the implications of CUDA — that GPUs could be used to speed up the training of neural networks, sometimes by orders of magnitude.

The prospect was intriguing — deep learning represented as radical a diversification as could be imagined for a company specialised in creating chips for computer gaming. With that opportunity, though, came concomitant risk. As Nvidia board member Mark Stevens told Crucible Moments, “Jensen always likes to say that ‘We’re investing in zero billion-dollar markets’”.

“This is the type of risk that, unless you’ve survived building a start-up, you’re probably allergic to doing.” — Jensen Huang, 2023

The pivot towards AI technology was a wholesale change for the business, diverting resources away from competing in computer graphics. However, an indication that this pivot might pay off in the long run came in September 2012, when Nvidia’s technology was used to underpin AlexNet — a convoluted neural network that, for the first time, demonstrated the feasibility of deep learning technology

Progress?

The immediate market reaction to Nvidia’s role in AlexNet was subdued. Unsurprisingly, in a world still reeling from the financial crisis few investors were optimistic enough to dive into the far-reaching implications of Nvidia’s pivot. Fast forward ten years, however, and the story is very different. Despite the uncertainty that surrounded the initial move, the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 catalysed a wave of public interest in large language models (LLMs), generative AI and the technologies that underpinned them.

Thanks to Huang’s gamble, Nvidia was, in the words of Jon Maier, Chief Investment Officer at Global X ETFs “the only game in town in terms of GPU makers”.

One suspects that, in retrospect, Huang does not regret the decision to leave his comfortable job at LSI Logic to start a speculative computer chip business with Malachowsky and Priem. However, when your vision is tied so inextricably to the ‘next version’, the end goal is always ahead.

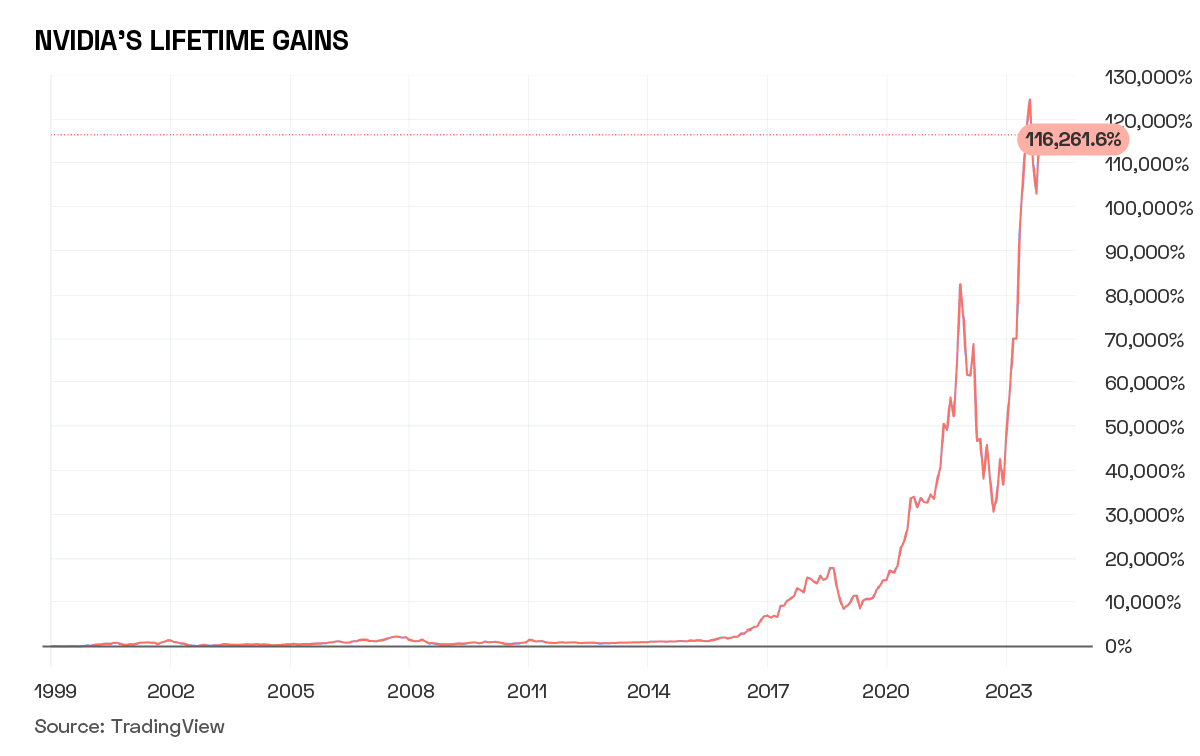

116,200%

In the 12 months since ChatGPT’s launch on 30 November, Nvidia’s share price gained 176.5%. In just under 25 years since its IPO, Nvidia’s gains are over 116,200%, and it has become one of only six companies to boast a trillion-dollar-plus market cap.

Unsurprisingly, the stock is held by a wide range of ETFs. These include AI ETFs such as the Global X Artificial Intelligence and Technology ETF [AIQ], semiconductor ETFs such as the iShares MSCI Global Semiconductors UCITS ETF [SEMI], and — fittingly, given where Huang and his co-founders began — video gaming ETFs, such as the VanEck Video Gaming and eSports UCITS ETF [ESPO].

Disclaimer Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

CMC Markets is an execution-only service provider. The material (whether or not it states any opinions) is for general information purposes only, and does not take into account your personal circumstances or objectives. Nothing in this material is (or should be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by CMC Markets or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

The material has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Although we are not specifically prevented from dealing before providing this material, we do not seek to take advantage of the material prior to its dissemination.

CMC Markets does not endorse or offer opinion on the trading strategies used by the author. Their trading strategies do not guarantee any return and CMC Markets shall not be held responsible for any loss that you may incur, either directly or indirectly, arising from any investment based on any information contained herein.

*Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and can change or may differ in a jurisdiction other than the UK.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy