From the iPhone to AI, a succession of new technologies have completely overhauled how the world works. It may seem that they happen overnight, but these major disruptions often represent a tipping point where innovation reaches critical mass.

Identifying disruptive trends before they reach their full potential represents one of the best opportunities for thematic investors.

Research shows that innovative companies tend to outperform their less innovative counterparts. According to J. P. Morgan, five of the 21st century’s biggest disruptors — Alphabet [GOOGL], Amazon [AMZN], Apple [AAPL], Meta [META] and Microsoft [MSFT] — posted median revenue growth of 22.5% over the past 15 years, compared to 3.1% for the S&P 500, and their shares outperformed the index by approximately 19 percentage points annually.

This series of articles from OPTO asks: How can investors harness disruption and identify critical tipping points? What are the stocks with the capacity to drive lasting change in markets?

In Search of Answers

Alphabet, more commonly known by the name of its flagship search engine, Google, started life (like so many successful start-ups) as an attempt to solve a problem: how to find relevant information on this new-fangled phenomenon, the ‘internet’.

During the early 1990s, the internet was rapidly gaining popularity across the world, and was already becoming a vast repository of information. The problem was, with so much information available, finding what you wanted was tricky.

In effect, you had to know the address of the website you wanted to visit in order to get there.

Various computer scientists identified this as a problem and set about attempting to categorise — or ‘index’ — the information on the internet. Two of the best-known early attempts were Yahoo and Ask Jeeves, though Archie, considered the world’s first-ever search engine, had been around since 1990 (predating the world wide web, which opened to the public the following year).

Now, search engines rely on three key pieces of technology: crawlers, indexers and searchers.

Crawlers are small computer programs that gather information from every website on the internet. Even by the 1990s, there was no way a human could cover all of the sites in existence: by the time of Google’s launch, there were already over two million, according to Statista.

Indexers organise the information gathered by crawlers. In so doing, they create an index — an enormous database of every website known to the search engine, categorised according to the words that appear on its various pages. Excite — a search engine which, like Google, was created by Stanford University students — was the first web directory to analyse site language in order to improve indexing.

Searchers scour an index to match the criteria in a search query to the content of a website. The goal of search engines, particularly early ones like Google and Ask Jeeves, was to find the best match possible to the query.

Ask Jeeves in particular stood out because it enabled users to search for information in a natural way — by asking questions — rather than merely by entering keywords. Up until the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, it was a strong contender in the search engine market.

Canning Spam

Google started life as Backrub, a project conceived by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, two computer scientists at Stanford University.

Their breakthrough was to analyse the links between websites as a means of determining the relative importance of any given page. In theory, the more sites that linked to a given website, the more important (and reliable) that website was.

One of the biggest problems this solved was web spam. Other search engines relied on meta tags that were easy for 1990s SEO experts to manipulate, reducing the relevance of the sites that were returned. Links to other sites, however, effectively served as a vote of confidence in that site, and the anchor text in the link signposted how the linked site should be indexed.

This made Google (which the pair re-named after googol, a mathematical term, when they received $100,000 from Sun Microsystems co-founder Andy Bechtolsheim to incorporate in 1998) far superior to its competitors at directing its users towards the information they wanted to find.

Google’s technology hasn’t stayed static, however. The search engine’s algorithm is constantly tweaked in order to stay ahead of SEO expert manipulations, and to ensure that the results it serves users are the most relevant to their needs.

Adding Value

The quality of its search results quickly propelled Google to the top of the search engine leaderboard.

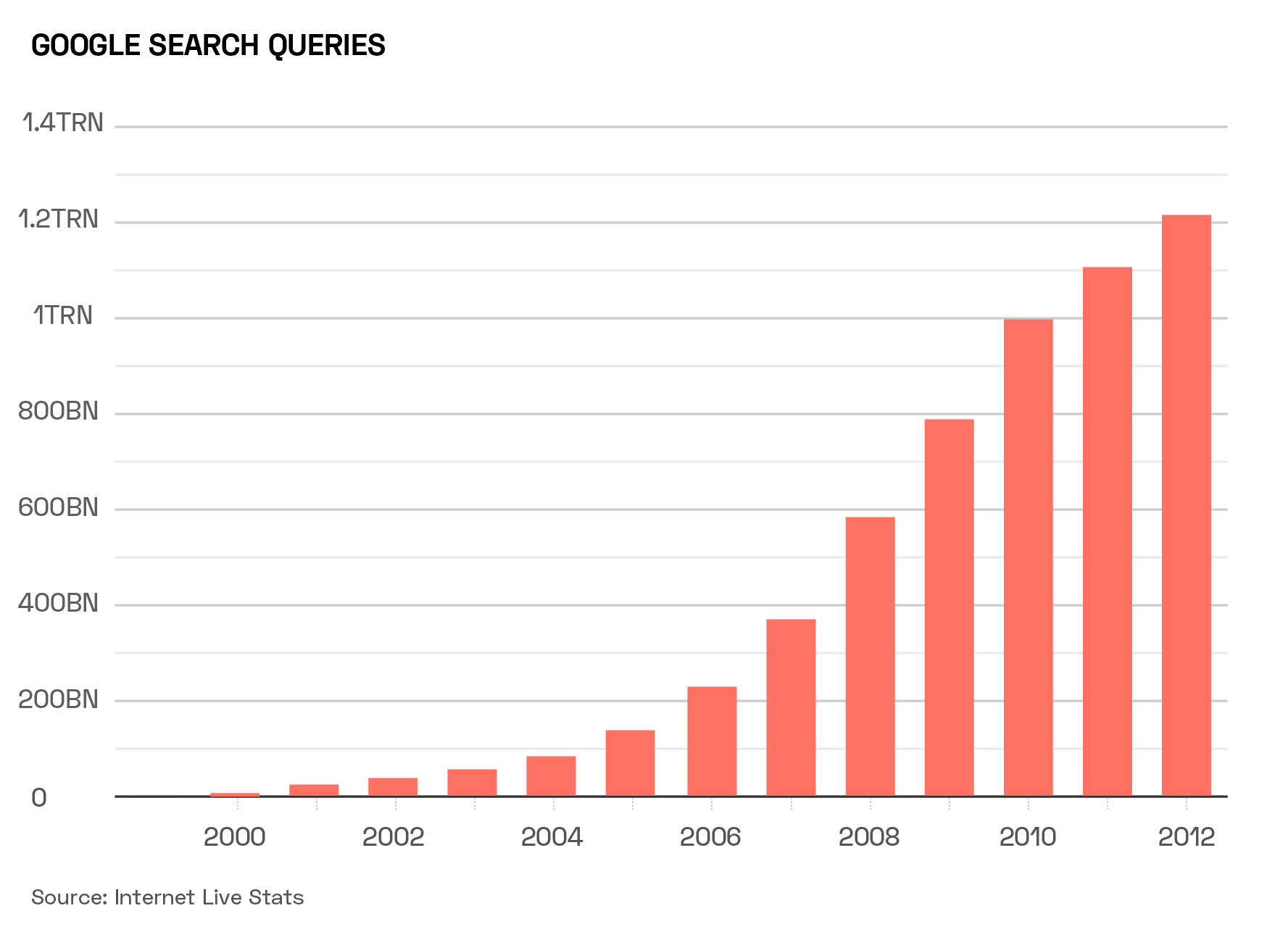

In 1998, the year of its launch, Google handled 10,000 searches per day. The following year, this rose to 3.5 million, and by 2000 the number was 18 million. That same year, it became the world’s largest search engine, boasting an index of over one billion websites.

Yahoo adopted a strategy of ‘If you can’t beat ‘em, buy ‘em’, integrating Google Search as its default backend search engine in 2000, before unsuccessfully attempting to buy the company for $3bn in 2002. In 2004, Yahoo stopped integrating Google Search in favour of its own search technology.

While VC investors including Sequoia Capital poured money into Google, monetisation was a key medium-term goal. As with most of the internet pioneers that thrived following the dot-com bubble, the solution was advertising. Google started selling adverts associated with particular search terms through Google AdWords in October 2000.

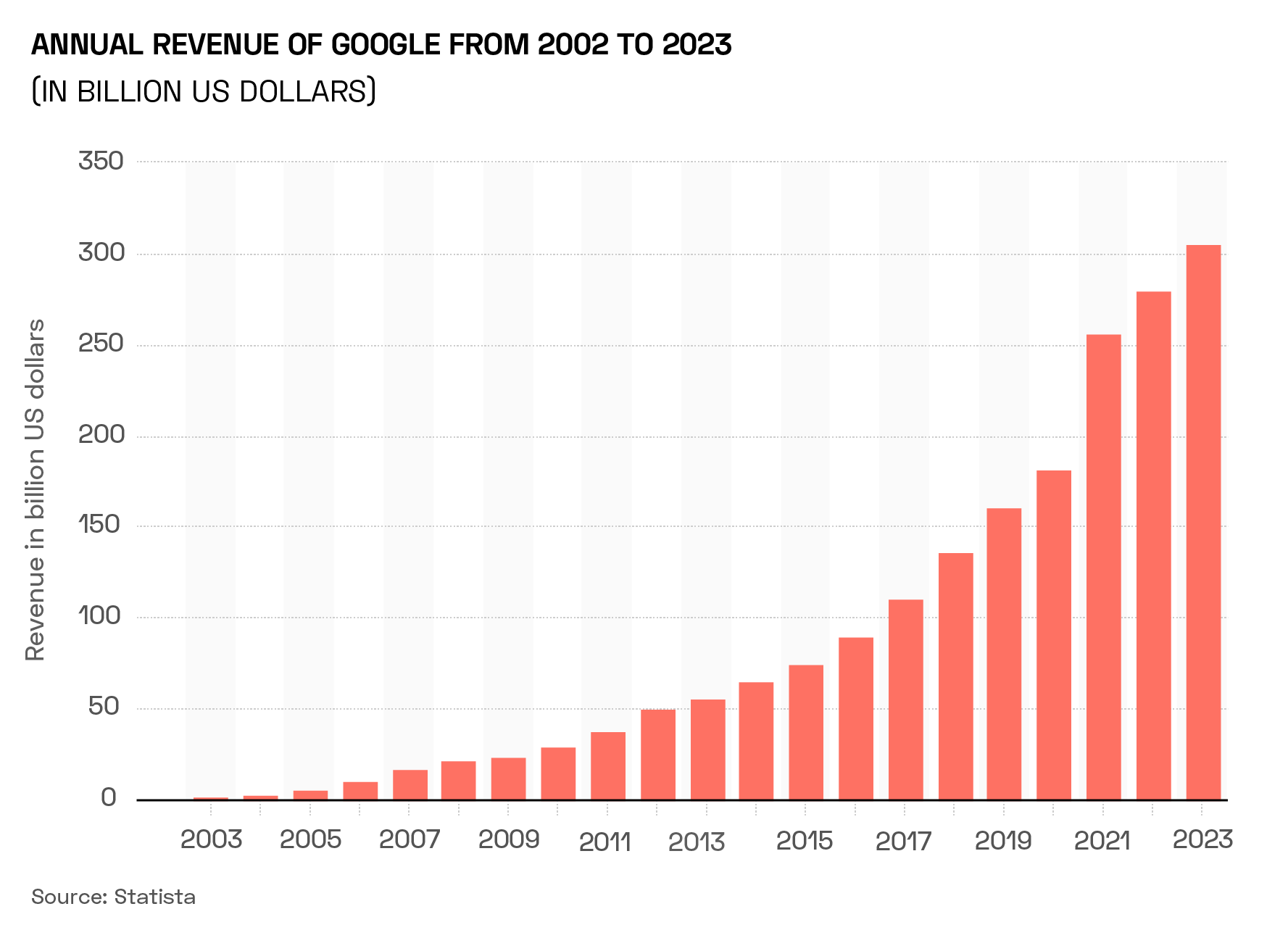

The impact was dramatic: in 2003, Google’s annual revenue shot up 275% year-over-year to $1.5bn, and passed the $10bn mark just three years later.

Despite Alphabet’s diversification efforts, nearly 80% of its revenues still comes from adverts on Google Search and YouTube.

GOOGL’s Growth

By 2004, Google was establishing itself as one of the biggest companies on the internet, and was ready to go public. Its shares were priced at $85, giving it a valuation of approximately $24bn At the time, Yahoo’s market value was approximately $39bn.

In 2020, Alphabet — the moniker for Google’s parent company as of 2015 — blew past $1trn, and its market cap sits at $1.8trn as of 13 February.

Even after falling from the highs it registered during the pandemic technology boom, Alphabet’s stock has soared. During 2023, its status as one of the ‘magnificent seven’ stocks that were closely associated with the AI boom propelled the stock to new heights, posting its all-time highest closing price of $153.51 on 29 January.

The stock has drifted down 3.9% since then, however, following an earnings report that failed to meet investors’ giddy expectations.

Jeeves Retires

Google’s effectiveness helped it to obliterate the competition; as of July 2023, the search engine holds nearly 82% of the global search market, according to Statista.

Ask Jeeves was wound down in 2006, and replaced with the more generic Ask.com.

However, as Charlie Warzel wrote in The Atlantic last year, Ask Jeeves might have had the right idea all along.

With the launch of ChatGPT in 2022, generative AI chatbots have been catapulted to popularity as a means of trawling the internet’s bank of information, many of them with distinct personas. As conversational web browsing looks set for a return, perhaps the suited butler is too.

Yahoo survived to be purchased for $4.5bn by Verizon [VZ] in 2017, and it now controls less than 3% of the global search market. Noteworthy alternatives to Google include Microsoft’s Bing as well as Baidu [BIDU], often referred to as the ‘Google of China’.

Baidu is a highly diversified business, with units dedicated to innovative areas of research such as AI and autonomous driving. In this regard, the comparisons with Google are especially apt.

Since reinventing the way we navigate the internet, Page and Brin’s business has kept itself at the forefront of innovation; indeed, the rebrand to Alphabet specifically aimed to encapsulate the multifaceted nature of the organisation.

The Alphabet umbrella covers names such as DeepMind and Waymo — companies already inventing the disruptive technology of the future.

Disclaimer Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

CMC Markets is an execution-only service provider. The material (whether or not it states any opinions) is for general information purposes only, and does not take into account your personal circumstances or objectives. Nothing in this material is (or should be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by CMC Markets or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

The material has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Although we are not specifically prevented from dealing before providing this material, we do not seek to take advantage of the material prior to its dissemination.

CMC Markets does not endorse or offer opinion on the trading strategies used by the author. Their trading strategies do not guarantee any return and CMC Markets shall not be held responsible for any loss that you may incur, either directly or indirectly, arising from any investment based on any information contained herein.

*Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and can change or may differ in a jurisdiction other than the UK.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy